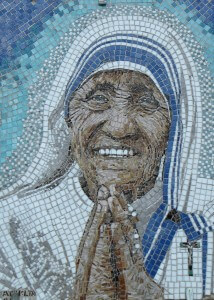

The private writings of Mother Teresa, published in Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light, are profoundly revealing of the interior life of a modern saint, inspiring and even dramatic (I found it a page-turner!). But even those of us who love Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity may be somewhat disturbed by the depth of her pain and loneliness, and the lengthy duration of her interior trial.

The Letters, the first feature-length theatrical biopic on Mother Teresa attempts to convey the inner life of Mother Teresa. Time Magazine called it a “50-year crisis of faith” and atheist Christopher Hitchens considers it further evidence for God’s absence. This last is ironic: why would Hitchens believe the testimony of someone he considers a fanatic?

It is not surprising that the media and unbelievers are confounded by the discovery that Mother Teresa experienced a relentless spiritual darkness, hidden from the world (and even from her own congregation), who saw only her characteristic good cheer and abundant good works. We expect this lack of understanding; they are “foolish and senseless people, who have eyes and see not, ears and hear not” (Jer 5:21).

But if we are honest, we don’t fully understand it, either.

Father Brian Kolodiejchuk, M.C., postulator for the cause of Blessed Mother Teresa’s canonization, offers a glimpse into the secret life of Mother Teresa—behind the dedicated apostolate, the tender service of the poor and forsaken, and her ubiquitous smile. He focuses specifically on three critical aspects of her spiritual life: the private vow to do whatever God asked of her (under pain of mortal sin) when she was still a Loreto nun, the mystical experiences that accompanied the “call within the call” (inspiration to found the Missionaries of Charity), and the nearly 50 years of spiritual “darkness.”

For those who are feeling abandoned by God, or merely stumbling along in the dark, learn about this saint who offers hope amid darkness and despair.

The call

For 17 years, Mother Mary Teresa had been happily serving Christ as a Loreto Sister in Calcutta, and was headed to a retreat in Darjeeling, when she heard the “voice” of Jesus beseech her: “Come, come, carry Me into the holes of the poor. Come, be my light.” Christ wanted Indian nuns, nuns who were like the poor themselves, “full of love nuns covered with My Charity of the Cross—Wilt thou refuse to do this for Me?”

Because of her private vow never to refuse anything that Jesus asked of her, she immediately took action. Following proper channels, she went first to her spiritual director and then to the archbishop of Calcutta, Ferdinand Perier. Not knowing about her private vow, the archbishop at first thought Mother Teresa was generous and gifted, but also “hasty” and “a bit exaggerated, maybe excited.”

Both her spiritual director and the archbishop urged her to continue to pray, to remain in obedience. The process of waiting seemed interminable to Mother Teresa, and she pestered the archbishop with letters, even insisting that it should not be difficult for him to approve immediately the founding of the new order. After all, she pointed out, the foundress of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary did not experience much trouble: “Overnight 20 nuns free to lead the Franciscan life—But in their case the Bishop was the acting factor.” The archbishop chastised her gently and explained that the process was not as simple as she thought. “[M]y dear Mother, you must also take my side now and then.” Finally, after due prayer, reflection, and consultation with theologians, he discerned that the call was genuine and the work was approved.

After waiting for two years, on December 21, 1948, Mother Teresa went alone, with no money or followers, into the ravaged streets of Calcutta. There were plenty who preached the kingdom to the wealthy of India, but only the Missionaries of Charity would serve the poorest of the poor. “I went for the first time to the slums—my first meeting with Christ in His distressing disguise.”

Immediately, young women were drawn to the new congregation. Mother Teresa herself was a dynamo in the physically taxing apostolate and in forming her new members spiritually. She emphasized the importance of serving the poor with a cheerful disposition, of selflessly serving the Lord. She wrote to the archbishop, “I want…to drink only from His chalice of pain…”

She did not realize what this would entail.

The chalice of pain

Almost as soon as Mother Teresa started “the work,” as she referred to it, she began to experience an intense spiritual darkness: her heart was cold, empty. From the time she was a small child, she had had a special love for Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament, but now she felt nothing. “How cold—how empty—how painful is my heart. Holy Communion—Holy Mass—all the holy things of spiritual life—of the life of Christ in me—are all so empty—so cold—so unwanted.” She had hoped to identify with the poor, leading a life of absolute poverty—and she found that her interior life was like the lives of the poor she served: unwanted, unloved, forsaken.

“If there be God—please forgive me—When I try to raise my thoughts to Heaven—there is such convicting emptiness that those very thoughts return like sharp knives and hurt my very soul.”

Many readers will find encouragement in the fact that, when we experience interior trials and even desolation, we can steadfastly cling to our faith and remain firmly committed to serving God and others. But, for many others, even people of faith, the thought that Mother Teresa experienced such unrelenting interior desolation is deeply troubling.

Mother Teresa knew that she should not trust her feelings—the feeling of pain, coldness, and loneliness, the lack of sensory consolations. But her experience of darkness extended even further: “Darkness is such that I really do not see—neither with my mind nor with my reason.—The place of God in my soul is blank.—There is no God in me.—When the pain of longing is so great—I just long and long for God—and then it is that I feel—He does not want me—He is not there.—Heaven—souls—why these are just words—which mean nothing to me.—My very life seems so contradictory. I help souls—to go where?—Why all this? Where is the soul in my very being? God does not want me…I long for God…and yet there is but pain.”

Over and over she expressed this painful longing without sensing—or even knowing—God’s presence, yet her will was always firmly attached to God’s will, and she always remained certain that the “work” was God’s work. The private vow never to refuse God anything kept her going through this painful experience of God’s absence.

The dark night

Mother Teresa’s spiritual directors have proposed that she was experiencing the “dark night of the soul” as described by Saint John of the Cross. Mother Teresa’s writings certainly fit the description of the dark night. The purgative dark night of the senses detaches us from sensible things and prepares the soul for the prayer of union. The night of the spirit detaches us from even spiritual consolations, imperfections, and all self-love. The soul experiences a terrible longing for God which is all the more severe, if she has ever experienced a mystical union with God—which Blessed Mother Teresa did experience early on—and there are temptations against faith and hope, and an inability to pray. It is an intense purifying of the soul, a purgatory on earth.

“If there is hell—this must be one. How terrible it is to be without God, no prayer, no faith, no love—the only thing that still remains—is the conviction that the work is His.”

Mother Teresa found herself on many occasions unable to speak about the difficulty to her spiritual directors or confessors: “Our Lord has taken even the power of speech.” Perhaps this was fortunate, for as Saint Teresa of Jesus of Avila wrote about her own experience, it was often a “torture” to deal with confessors and spiritual directors. “Is it credible that she will be able to say what is the matter with her? The thing is inexpressible, for this distress and oppression are spiritual troubles and cannot be given a name.” (6th mansions ch I).

Accept what He gives and give what He takes

Mother Teresa receiving the Medal of Freedom