Saints aren’t born, they are made, as one writer observes.

Saints grow out of the rich soil of a vibrant Catholic culture and how it is lived out in their families, parishes, and communities. This especially holds true for the saint known as the ‘Little Flower,’ St. Thérèse of Lisieux, behind whom stand the two saints who were her parents, Sts. Louis and Zélie Martin.

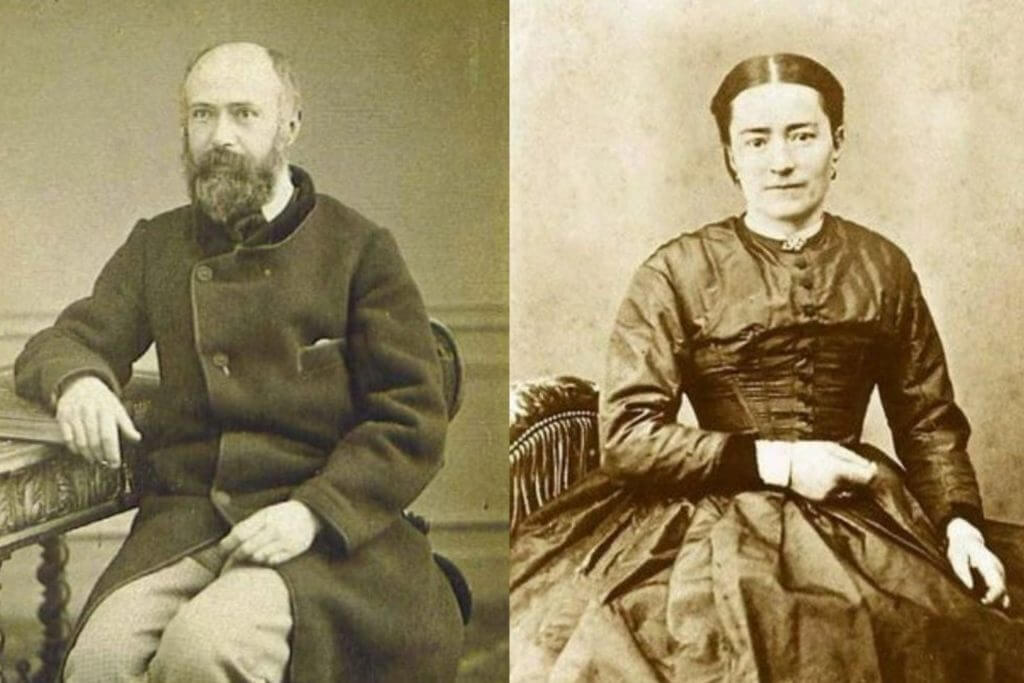

Louis and Zelie were married on July 13, 1858 and would go on to have nine children, with St. Therese the youngest. “I love children to madness. I was born to have them,” Zelie once said.

But if Zelie and Louis had pursued what they thought was their initial vocation, their marriage would never have happened.

They each thought they were called to religious life.

Born in 1823, Louis was raised in a devoutly Catholic military family. “He absorbed the sense of order and discipline that army life engenders. His temperament, deeply influenced by the peculiar French connection between the mystical and the military, tended toward things of the spirit,” as one account puts it.

When he was 22, Louis discerned a calling to the Augustinians. He was drawn to the Great St. Bernard Hospice in the Alps and their life of prayer and rescuing hikers. But he was not allowed to enter because he didn’t know Latin—and his efforts to learn it failed.

Like Louis, Zelie, who was born in 1831, came from a family marked by its patriotism and faith: one family story told of a grand uncle, a priest, remembered for his deep reverence for the Eucharist. Once, during the French Revolution, he was attack by a band of pro-revolutionary forces. The uncle, Father William Marin-Guérin, fought off the men—but not before he made sure the Eucharistic wafer he had been carrying was safely out of the fray on a rock. “Now, Jesus, You can take care of Yourself; let me take care of myself,” he said.

Also like Louis, Zelie felt a calling to religious life, and sought to join Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul at the Hotel-Dieu of Alencon, a hotel where she would be caring for the sick. But she was turned away for health reasons.

"He is the one I have prepared for you," Zelie sensed when she met Louis.

Their paths finally crossed when Louis was 34 and Zelie was 26. By then both had thought they were destined for a life of celibacy and consecration to God, according to one short biography by Father Antonio Sicari, OCD.

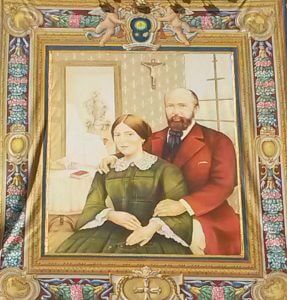

But that all changed when they met. As they were walking over a bridge, Zelie sensed a voice within her saying, “He is the one I have prepared for you.” Three months later, in 1858, they married and merged their watch and lace-making into one business, according to Sicari.

From the start, their marriage was marked by chastity and obedience to God. Later, after his death, a card was discovered among Louis’ possessions with an underlined note warning against desire for the conjugal act without the desire for children.

As with their marriage, the Martins entrusted their business to God. “Look, I’ve been telling you to take it easy,” Louis wrote to his wife while in Paris. “You’re working too hard; you’re tiring yourself out. We’ll work hard, but God will take care of the rest. We’ll build up a small, prosperous business, but don’t be killing yourself in the process.”

As in many cases, suffering makes saints. The Martins lost four of their nine children.

They would go on to endure many hardships and tragedies. In 1870, the Franco-Prussian War broke out and the Martins, who lived in Alençon in Normandy, found themselves living under an occupation, with nine soldiers forcibly boarding at their house. But the Martins loved their enemies: when one soldier who had been staying with them faced execution for stealing one of their watches, Louis pleaded for his life, saving him.

The Martins also suffered through the deaths of four of their nine children—three at age 1 or younger, and the fourth, Hélène, when she was 5. “I haven’t a penny’s worth of courage,” Zelie once said, amid the loss of so many children.

She took the death of Hélène particularly hard. “That which hurts me the most and which I can’t get over, is that I didn’t better understand her condition...I had the doctor come and he told me that he found no obvious illness, and that he saw no need to come back, unless she became worse,” she wrote. And yet somehow she persevered in her faith.

Despite such heartbreak, Zelie did not consider her deceased children ‘lost.’

“My children were not lost forever; life is short and full of miseries, and we shall find our little ones again up above,” she wrote.

Zelie herself would die at the relatively young age of 46, in 1877, when Thérèse was 4.

Both her parents had a powerful influence on Thérèse’s faith and pursuit of holiness. In Story of a Soul she wrote that at a later time in life, “I realized that to become a saint one must suffer a great deal, always seek what is best, and forget oneself.”

Even though Louis was left to raise his family alone, he did so with great joy, even asking for more suffering later in life.

As she grew up, Thérèse’s father made a deep impression on her. During the homily at Mass, she looked not at the preacher but at her father because she could “read so much in his face.” “As he heard the eternal truths, he seemed as if he had already left the earth,” she recalls in her autobiography.

On the day that she chose to tell Louis of her decision to enter the Carmelites, Thérèse came home to find her father seated in the garden listening to the birds “singing their evening prayer.”

“There was a look of Heaven on Father's noble face, and I felt sure his heart was filled with peace,” Thérèse writes.

Despite what he had already been through, Louis welcomed further suffering from God. At the Church of Notre Dame Alençon, where he had been married, Louis prayed, “It is too much, my God. I am too happy. This is not the way to Heaven; I want to suffer something for You, and I offer myself.”

Louis was hit with a series of strokes, accompanied by dementia. He had a tendency to wander off from his home without telling anyone. His deteriorating mental health—caused possibly by a vascular disease known as arteriosclerosis—led him to spend the final three years of his life in a mental asylum. On her last visit with him, he couldn’t speak, but instead pointed upwards to heaven.

“Heaven, with all its wonders, is now his,” Thérèse wrote after his death. "[T]he ties which bound his guardian angel to earth are broken, for angels do not remain here below once their task is done. They wing their way back to God. … But the difficulties seemed insuperable.”

Just three years after Louis's death, Thérèse joined her parents in heaven.

Thérèse did not have to wait long before joining him and her mother. She died at 24 in 1897, three years after his passing. A quarter of a century later, in 1925, she was canonized.

As the Church has gotten to know Thérèse better, it has grown in its appreciation for her parents. In October 2015, Sts. Louis and Zelie Martin were canonized. They are reportedly the first married saints who had children to be canonized together.

In the homily at their canonization, the couple was praised for their role in the development of Thérèse’s own call to holiness.

“The holy spouses Louis Martin and Marie-Azélie Guérin practiced Christian service in the family, creating day by day an environment of faith and love which nurtured the vocations of their daughters, among whom was Saint Therese of the Child Jesus.”